Section One: Flying in Canada

Both the AOPA member’s section website and NavCanada’s website contain a wealth of information on flying in Canada. Cirrus pilots considering a trip to Alaska should consult both of these resources.

The FAA website offers an overview on flying in Alaska and specific tips for various towns and regions of Alaska.

This section of the Alaska Flying Guide aims to provide Cirrus pilots with additional “news you can use” based on practical experience, rather than information that is readily found online elsewhere.

Radar Coverage: NOT!

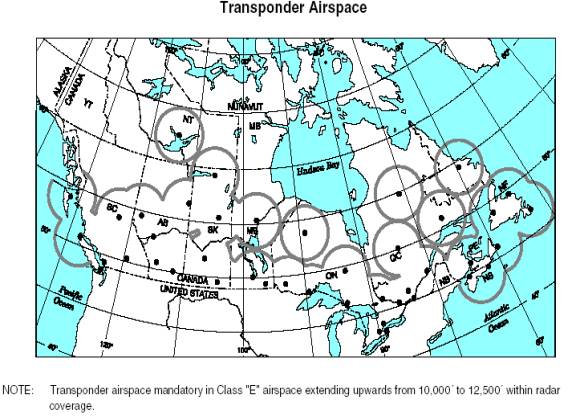

- First time pilots across the vast expanses of Canada are surprised to learn that most Canadian airspace west of Toronto does not have radar coverage. The same is true for nearly all of Alaska. Consequently do not expect to receive a transponder code, even if on an IFR flight plan, throughout most of the trip across Canada and Alaska. VFR flight following is rarely available. Squawking 1200, even for an IFR flight, is rather customary.

- Major cities enroute to Alaska, such as Winnipeg, Regina, Edmonton and Vancouver (as well as Anchorage), do have radar coverage, and ATC will require a working Mode C transponder, and will provide a transponder code (and VFR flight following), within 25-50 miles of those cities. Outside of those small areas, however, you’re on your own. On the other hand, there is very little general aviation traffic across the vast expanses of Canada (other than perhaps on the Alaska Highway route). Flying with at least one buddy aircraft and communicating with each other on 123.45 is highly recommended, both as a safety measure and to exchange information and ideas on weather and terrain as the flight progresses.

- This map shows just how sparse radar coverage is in western Canada (especially below 12,500 feet): in fact, it is basically non-existent.

Common Frequencies

- VFR flight in uncontrolled Canadian airspace (which is virtually everything outside of the major cities such as Winnipeg, Regina, Edmonton and Vancouver) uses 126.7 everywhere to communicate with ATC. You can call that frequency to get current weather at a destination airport or to close a flight plan. When flying VFR, this frequency should be monitored at all times.

- The Canadian IFR charts recommend that 126.7 should also be continuously monitored whenever practicable while flying IFR in uncontrolled airspace and when flying VFR in controlled airspace, unless another frequency is noted for a given area. The wisdom of this advice was evident during a flight of Cirri across the Yukon Territories when a 767 pilot announced that he was about to commence a large fuel dump (fortunately that plane was 50 miles away).

- Plane-to-plane communications in Canada and Alaska are best accomplished on 123.45. Depending on terrain, it is possible to maintain contact with other planes up to 75 miles away.

A Word About VFR Flying and Charts

- A trip to Alaska through Canada from June through August should provide ideal VFR conditions: high cloud bases and excellent visibility. The biggest risk is forest fires, which are rare but can cover thousands of square miles and create solid IFR conditions. Unfortunately, because they are rare, there is little in the way of fire-fighting equipment, so a big fire can rage for weeks. The choice, therefore, is to either stay on the ground or be prepared to fly IFR.

- Expect to fly VFR most of the time in Canada and Alaska: think about whether you’ll be comfortable exploring the scenery and terrain from lower altitudes (e.g., 1,500’ to 2,500’ agl), or whether you’d prefer to be much higher up (e.g., 6,500’ to 10,500’ agl). This Alaska Flying Guide provides insights on both situations, and ultimately its up to each pilot to determine what their comfort level.

- Don’t expect to find a local source for charts or plates. Unlike the continental US, most FBOs do not ordinarily carry a supply of current aeronautical information. Therefore, it is imperative to bring along all the VFR and IFR charts and plates that you might expect to use.

- Canadian airspace rules are quite similar to the US rules. But be prepared to receive a bill from NavCanada after you return home for using their airspace and services.

Fly IFR Like When FDR Was President

- ATC manages IFR flights in non-radar covered areas based on altitude separation and pilot reports to ATC over specific fixes: just like in the 1930s (or the 1960s, if your memory is fading). When flying IFR with a group over mountains (e.g., the segment from Whitehorse, Yukon to Anchorage, Alaska), expect each plane to be assigned an altitude ranging from 12,000 to 16,000 feet and/or to be spaced at least 20 nautical miles apart. Release for departure is therefore authorized every ten minutes, and ATC clearance cannot be requested until the preceding plane has taken off. Contrast this practice with the U.S., where a clearance (subject to release) can typically be obtained before taxiing. An enroute change in altitude will not be allowed by ATC if your plane is less than 20 miles behind another aircraft in the group that is flying at the altitude you wish to occupy.

- Because radar coverage is so rare over most of Canada, if an IFR approach into an airport is necessary due to IMC conditions, do not be surprised if ATC issues holding instructions for 15-45 minutes while other aircraft ahead are sequenced into the approach. And do not request or expect vectors to final: there’s no radar, so the best ATC can provide is clearance to a fix. In other words, think 1930s (or an IPC exam) and expect to fly the full approach, including any procedure turn or course reversal.

- NDBs are still widely used in Canada, both for enroute navigation and for instrument approaches. And DME arc instrument approaches are far more common in Canada than in the US, so be prepared to fly these as well. The Garmin database for North America includes all this information, so neither is problematic.

Fly VFR Using the Recommended Routes

- The Canadian VFR navigation charts contain blue diamond trails that delineate commonly-used/recommended VFR routes. For example, the Alaska Highway and Trench routes described in Section Two of this guide are easily tracked via the VFR routing shown on the published Canadian VFR charts. Typically these follow a valley between the mountains, and show the height above sea level for mountain passes.

- Like US charts, the Canadian VFR charts also show a maximum elevation figure for a given quadrangle. This is the highest known feature in each sector, including terrain and man-made obstructions. These should be used as a reference value in determining how low or high a pilot can comfortably fly across mountainous terrain.

- The Canadian VFR charts have a cautionary note accompanying many of the commonly-used/recommended VFR routes: “Route subject to rapid weather change. Altitude should permit course reversal.” Often this cautionary note will recommend a minimum VFR altitude between two points on the route.

Finding the Right Airport Identifier in Canada

- Finding the ICAO airport identifier in Canada for input into the Garmin can be a challenge. This is because, unlike US charts, the ICAO airport identifier is not printed on any of the official Canadian charts. It is, however, noted in small letters on the upper right hand corner (about 1” from the top) on the government-published IAPs (instrument approach plates). One useful hint is to simply add the letter C to the VOR identifier near an airport: this usually works in identifying the adjacent airport. For the less adventurous, Canadian customs’ website has a listing of many airports, along with the proper identifier. Or reference NavCanada’s regional list of airports at the bottom of their TAF/METARs look-up page. Or see the excerpts from the Airport Facilities Directory in Section Five, which contains information on all of the Canadian airports mentioned in this Alaska Flying Guide. Or use this cross reference list which contains all Canadian airports, but in alphabetical order by identifier. Finally, AOPA’s free online flight planning software provides the proper identifier information when laying out a flight plan. (As an aisde, DUATS software is generally inadequate for flight planning purposes across Canada because it doesn’t seem to recognize any of the published airways.)

- If all else fails, you can refer to the latitude/longitude coordinates in the attached list of Canadian airports, navaids and waypoints, and manually input a given location as a user-defined waypoint on the Garmin 430.

- Jepp charts include the appropriate ICAO aiport identifier, and you can order a “trip kit” for Canada and Alaska that includes all of the approach and enroute charts for a trip.

Weather Information and Flight Plans

- To obtain a weather briefing in Canada, or to file an IFR or VFR flight plan, call 1-866-WX-BRIEF (1-866-992-7433). Or go the NavCanada’s weather web site for online information. Major airports have a flight service office on the field, and virtually every other airport has a phone kiosk on the field for this purpose. (As an aside, satellite phones will generally work in Canada, but satellite calls are often dropped after 30-60 seconds in Alaska.)

- Use the ICAO flight plan for all VFR and IFR flights in Canada, rather than the US flight plan form.

- Airports in remote areas of Canada do not generally have ATIS, ASOS or AWOS information. If flying on an IFR flight plan, the approach controller will read the terminal weather to you prior to landing. On a VFR flight plan, contact the local radio controller on 126.7 to request a weather update for destination airport.

- All cross-country flights in Canadian airspace must be conducted under either an IFR or VFR flight plan (e.g., more than 25 nm from the departure airport). A VFR flight plan is automatically activated at the designated departure time, so remember to close the flight plan upon landing, or by contacting 126.7 in uncontrolled airspace for the nearest radio connection to ATC. Remember to contact 1-866-WX-BRIEF if a VFR flight is delayed or cancelled, since the flight plan opens automatically and failure to advise flight service might otherwise trigger unnecessary rescue efforts.

Canadian Customs: Just One Number to Remember

- Before departing the U.S. for a landing in Canada, contact Canada’s Border Service Agency, at 1-888-CANPASS (1-888-226-7277). They must be called two to forty-eight hours before the planned arrival time at an airport of entry, and again upon arrival. Once they have your tail number in their computer system, they will often waive any customs inspection, even at a major city airport. But advance notice is still always required. General information on Canadian customs is available at the Canada Border Service website.

- If you register in advance with Canada’s Border Services Agency under their private aircraft program, then you can bypass the normal “airport of entry” rules and land anywhere in Canada.

Home | Introduction |

One: Flying in Canada | Two: Getting

There

Three: Things to Do in Alaska | Four: Getting Back to the US from Alaska | Five: Equipment List

Six: Charts and Aeronautical Information | Photo Gallery: 2004